So sad and disappointing to find out that the human rights organization, Memorial, is now an illegal entity in Russia. Why? Supposedly, Memorial has received foreign agent status after receiving funding from abroad. Technically, the NGO is supposed to acknowledge this funding on every web page, instead of just on the home page. Memorial also received internal funding, in tiny amounts, by family members oppressed during the Stalin years.

|

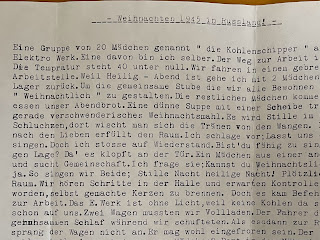

| Family members affected by Stalin. Grandparents far right. |

It’s like Putin and his cronies have decided that my grandparents, whose stories I only discovered after the collapse of the USSR, never died because of Stalin’s liquidation of the kulaks. It’s like Putin saying that I have no right to know why my mom became orphaned at the age of 12 out in Yaya, Siberia. It’s like saying my grandfather was not wrongly accused for treason under Article 58 and shot during the 1937/8 Great Terror. It’s like the Russian present is afraid of its Soviet past. Why would Putin deny his country’s atrocities? Because he wants his countrymen to be nostalgic for the good old days as a communist powerhouse. He wants to re-write history, but why? So he can affect the future?

Germany has accepted its dark Nazi past with numerous monuments, memorials and most importantly, education of the young. True, it took a full generation for the silence about Nazi atrocities to be broken and for the guilt to be admitted. But now we can look at Germany as a role model of how to reconcile the wrongs of the past and create a better present.

Here in Canada we have declared a national holiday on September 30th, as Truth and Reconciliation Day. It’s a tiny step . . . as is renaming schools, streets and removing colonial oppressor monuments. We here have our own horrendous past with indignities perpetrated through the residential schools. Our racism is still alive and well, as our jails and our poor neighbourhoods can attest, but we are acknowledging its existence. Secrets lose their power in the light.

Why is Putin silencing Memorial? Why is he so afraid of the truth? Memorial or not, inter-generational trauma is real. We see it on the streets of my city where I grew up seeing homeless drunks and being told that it was their race that was the problem not us—the colonizers.

My family members. . . grandparents, mother, aunts and uncles, were victims of Stalin’s atrocities. Putin can silence Memorial but he can’t silence our stories. We have to tell them. It’s too bad the year has to end on such an ominous note. May the new year bring positive change. Happy 2022 to us all!