Someone recently asked me whether it was my mom's voice or mine that expressed writerly ambitions in Tainted Amber.

While my mom regularly derided my interest in books as 'brotloße Kunst' or 'breadless art,' I've scavenged bits and pieces of her own words written in her hard-to-decipher handwriting. Just recently, I found, inside what I thought was an empty journal, pages called "Die Fahrt nach Russland, 1945" or 'The Journey to Russia, 1945.' Such a treasure which served to underline her oral sharings of those dark times. Crow Stone is based on her memories, after doing much background research.My mom actually had a piece published in Kanada Kurier a German-language newspaper, based here in Winnipeg. (It morphed out of the 1969 closing of Der Nordwesten.) I found Mom's yellowed newspaper article amongst her scattered papers, in between recipes and budget plans. Both newspapers were ubiquitous in our house when I was growing up. Now I scrounge to find copies! Here's a translation of her published piece about Christmas as a prisoner of war.

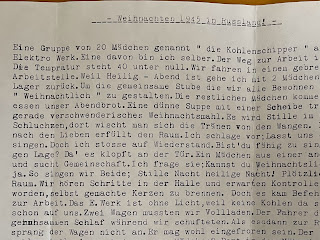

The Story of the Coal-shippers’ Christmas

by Else Schroeder

(translated & edited for flow and clarity from the German by Gabriele Goldstone)

A group of twenty girls, called the coal-shippers, is working at an electric energy plant near Kurgan and Chelyabinsk in the Urals. I am one of them.

The distance to work is about seven kilometers. The temperature is -40 degrees and we travel there in the back of a dilapidated truck. Because it is Christmas Eve, two other girls and myself go back to our camp early to warm up the room we all share and to decorate it to look a little bit festive.

When the rest of the girls return, we eat our evening meal: thin soup and a slice of dry bread – not a very satisfying, elaborate Christmas dinner!

Back in our barrack, it becomes quiet. Here you hear someone sobbing, and there someone wipes away a tear from her cheek. Homesickness and longing for loved ones fills the room. I suggest we sing some Christmas songs, but there is opposition.“Are you able to sing in this dreary place?”

There’s a knock at the door. A girl from another group is looking for company. I ask her, “Do you want to sing some Christmas songs?” She says yes, and so the two of us sing Silent Night, Holy Night.

Suddenly it’s dark in the room. We can hear footsteps in the hallway and expect an inspection. We had been told not to burn homemade candles. But instead, we receive orders to line up immediately to go back to work. The electric plant is out of power and needs more coal. The old truck is already waiting for us.

We head back out and fill up two lorries. The truck driver has a nice nap while we slave. Then, when it’s time to return to our camp, the truck won’t start. It’s probably frozen. Now what?

“Wait here until someone comes to get you,” is the order. The guard points to a building not too far away—a stall for animals. It’s filled with cows, sheep and even a donkey.

The night is cold, the sky, clear, starry. After the guard heads back to the main camp in his own vehicle, peace and quiet surrounds us. The animals are lying on their beds of straw, and us girls, tired and worn out from the cold and work, do the same, trying to get some sleep.

|

| Kurgan Area in the Urals. Wikimedia Commons |

Finally, it’s morning. Another truck fetches us for some breakfast and then it’s back to work again, back to shovelling coal.

That was my Christmas in the year 1945.

No comments:

Post a Comment