The stores, during these last days of December, are filled with shoppers looking for bargains during 'liquidation sales.'

Russia has a different take on 'liquidation.' Back on December 27, 1929, the Soviet government, under Stalin, passed the resolution to ‘liquidate the kulaks’ as a class.

|

| Sign says: Liquidate the kulaks as a class. Photo: Unknown. Thanks to Lewis H. Siegelbaum and Andrej K. Sokolov, GFDL <http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html>, via Wikimedia Commons |

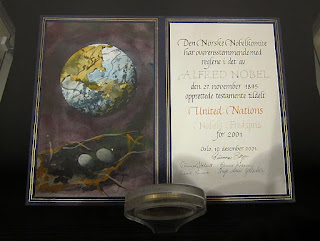

On December 29, 2021, the Russian government, under Putin, passed another liquidation law ... the resolution to liquidate Memorial, the human rights organization focused on victims of political repression.

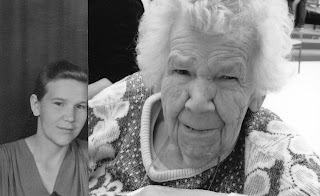

It took me twenty years to figure out my family history, repressed as it was under the Soviet regime. Finding it, proving it, left me feeling sad but started a healing process. 93 years after my mom’s family was broken apart, after the family’s windmill was lost; almost 70 years after my grandfather was killed, I'd found him. I'd found my family. But now the modern Russian government has rescinded that tragic past. Now it's illegal for people to remember their own history.

|

| My grandfather, a kulak |

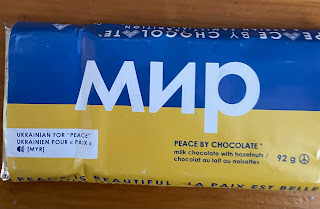

This year, 2022, Putin has a new set of liquidation laws. While still waiting for the final stamp of approval, new laws passed a first reading December 20, 2022, against ‘sabotage propaganda’. This is open to interpretation, but ‘liking’ an anti-Russian, pro-Ukrainian Instagram post could now be considered ‘sabotage’ with a prison sentence of 20 years or more. Putin’s about to ‘liquidate’ anyone. Just like ‘kulak’ became a convenient label for anyone seen as different; modern Russia targets internal threats with labels and laws.

|

| Dangerous windmill |

“The punishment for saboteurs will be as severe as possible,” said State Duma Chairman Vyacheslav Volodin, a member of Russia’s ruling United Russia party. (Moscow Times)

I’m afraid for a Russian friend of mine. Perhaps it’s best that we don’t connect. Our friendship could be her downfall. Our children’s book project about cuckoos and storks might somehow be seen as subversive. I wish I was joking.

Definitions:

Subvert: to destroy or damage

Liquidate: to eliminate

.jpg)

,_ermordete_Deutsche.jpg)

,_zersto%CC%88rte_Geba%CC%88ude.jpg)