Saw the re-mastered movie, Come and See, last week at Cinematheque a small, boutique-style theatre that showcases independent and international films here in our Exchange Distract. It came out originally in 1985.

Come and See is set in the forests of Belarus, in 1943, and focuses on the partisan movement. Some might consider the film a horror show, but it was in fact a war movie. It depicted animal cruelty, rape and violent death on the eastern front during the Second World War. According to the closing moments of the film, 628 Belarus villages were burned to the ground by the Nazis. Similar burnings happened in Ukraine. It’s no wonder a Ukrainian woman once spit in my face when I talked with survivors of such atrocities. I heard of how women and children were separated from the men, herded into barns and set ablaze.

I searched the internet for some stats on Ukrainian losses and found this: “... the world never heard about the Ukrainian village of Kortelisy which the Germans burned to the ground on September 23, 1942 and killed all its 2,892 population of men, women and children. There were about 459 villages in Ukraine completely destroyed with all or part of their population by the German Army with 97 in Volhynia Province, 32 in Zhitomir province, 21 in Chernihiv province, 17 in Kiev province and elsewhere. There were at least 27 Ukrainian villages in which every man, woman and child was killed and the village completely destroyed by the Germans. (Ukrainska RSR u Velykyi Vitchyznianiy Viyni, vol.3, p. 150). http://www.infoukes.com/history/ww2/page-20.html

_%D0%B2_%D1%87%D0%B5%D1%81%D1%82%D1%8C_%D0%B2%D0%B8%D0%B7%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B0_%D0%B3%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BB-%D0%B3%D1%83%D0%B1%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B0_%D0%9F%D0%BE%D0%BB%D1%8C%D1%88%D0%B8_%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%B8%CC%86%D1%85%D1%81%D0%BB%D1%8F%D0%B8%CC%86%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B0_%D0%93%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%81%D0%B0_%D0%A4%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BA%D0%B0_2.jpg) |

| public domain, Stanislaviv, October, 1941 |

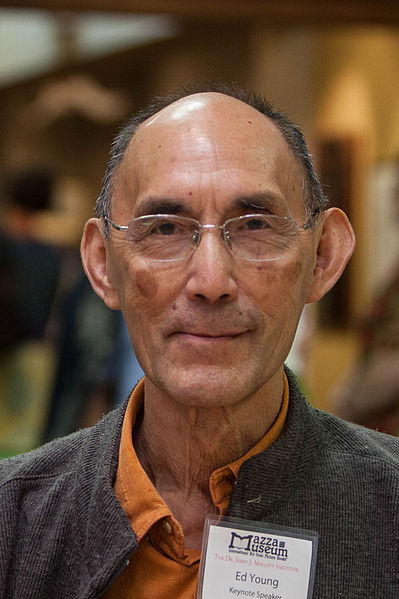

My father was sent to the eastern front in October, 1944. He never talked much about it — focusing his war memories on his earlier time in the Luftwaffe, until he crashed. I think his new position in the Military Police was to discipline the failing moral of the Wehrmacht. I know that he drove a motorcycle with a sidecar … like a Nazi in the movie. I felt quite uncomfortable watching those scenes, along with the others where the Nazis drink, loot, shoot, rape and sing. The father I grew up with liked to go fishing and hunting. He liked to build things and read books. He built model Junker airplanes with my brother. So excuse my obsession with that old war. It forms part of my identity.

|

| my dad, 1944 |

Last week our parliament honoured a 98-year-old Ukrainian-Canadian,

Yaroslav Hunka, who had supported the Nazis in Ukraine. Canada cringes with the political fallout and Poland demands his extradition. It would be fascinating to hear Hunka’s story. Why are we so eager to seek revenge on something that can never be revenged? Hunka would have been 20 years old at the end of the war. He would have grown up under Stalin’s Five-Year Plans, experienced the Holodomor. He might have seen the Nazis as liberators from the Soviets. He might have had to choose between two evils. Until we hear his story, we might hold off on judging him.

The film, Come and See, depicted the horrors of Nazi atrocities with gut-wrenching visuals. If 18-year-old Hunka played a role in those events he does not deserve honour. But neither does he deserve my judgement. I can only be curious. What's his story?

_%D0%B2_%D1%87%D0%B5%D1%81%D1%82%D1%8C_%D0%B2%D0%B8%D0%B7%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B0_%D0%B3%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BB-%D0%B3%D1%83%D0%B1%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B0_%D0%9F%D0%BE%D0%BB%D1%8C%D1%88%D0%B8_%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%B8%CC%86%D1%85%D1%81%D0%BB%D1%8F%D0%B8%CC%86%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B0_%D0%93%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%81%D0%B0_%D0%A4%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BA%D0%B0_2.jpg)